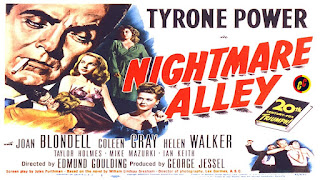

It is no surprise to hear that 1947’s Nightmare Alley, the first adaptation of William Gresham’s novel was a passion project for its leading man Tyrone Power. Tired of being the Hollywood heartthrob in swashbucklers and light romances, and having seen a darker side of life in WW2, Power for looking for something meaty to sink his acting teeth into, and found the decidedly anti-heroic part of the fast-talking born hustler Stanton Carlisle right up his (ha!) alley. Of course, it was not a simple matter to bag the part. Fox Studios’ head honcho Daryl F. Zanuck was against the idea of one of his top movie leads risking his box-office charisma with such an unsympathetic part. Tyrone’s persuasion and a bit of script doctoring to tone down the hard-boiled cynicism of the source story finally got his okay and the result was a remarkable film that straddles noir and even a little bit of horror.

When we first meet Stanton he is assisting at a small-time carnival sideshow where Zeena (Joan Blondell) and her alcoholic husband Pete (Ian Keith) do a psychic act powered by a secret code between them. While Zeena still loves her decrepit spouse she is not wholly immune to Stanton’s charms. An accident (or is it?) leads to Pete’s death and Zeena shares the secret code with Stanton who becomes her partner in the act. He in turn shares it with his child-woman lover Molly (Coleen Gray). Shortly after Stanton and Molly quit the carnival and tour as a stage psychic act in high-end clubs where a blindfolded Stanton amazes guests with his ability to guess their questions and answer them correctly. During this period, Stanton encounters the icy psychiatrist Lilith Ritter (Helen Walker), who first challenges him, but later becomes his accomplice in carrying out a larger-scale swindle with a rich man’s spiritual beliefs. Of course, Stanton’s karma catches up, and his elaborate schemes come crashing down upon him.

Stanton almost has a streak of self-destructiveness in how he trapezes from one con game to another, raising the stakes each time, with nothing by way of a safety net. The only constants in his outlook are his uneasiness / dissatisfaction with his current situation and almost feverish eagerness to set up a bigger, riskier scheme. Tyrone Power’s performance brilliantly reflects this, eschewing any easy sentimentality for this equal parts fascinating and frightening character; even the occasional depiction of a softer side works to add more dimension to Stanton and not have him be a stock villain.

Aside from Stanton himself, the film is pegged upon its female characters – Zeena, Molly and Lilith. While Zeena’s psychic is a con-game, she still has scruples (Hers is only a stage act, not a swindle). Interestingly she is a firm believer in the tarot, and her predictions with the cards foreshadow the film’s tragic events. Molly represents an unquestioning love, but even she is shocked by how far Stanton is willing to go in terms of snagging his prey. Lilith on the other hand turns out to be Stanton’s equal in ruthlessness. As a psychiatrist she surreptitiously records her clients’ sessions and provides Stanton with intimate details that enable him to “hook them”. It is hinted that she makes romantic advances to Stanton which he brushes away, and perhaps this is in her head as she betrays him once the roulette wheel starts to spin away from his grasp. As much as the script, Helen Walker’s performance brings the character chillingly alive from her first appearance to her final scene in which she almost gleefully reduces Stanton to a paranoid wreck. It is tragic that Walker’s movie career was short-lived on account of off-screen misfortunes (A history of alcoholism, and a driving accident in which a war veteran she had given a lift to was killed led to hostility from the public and disregard from the studios).

As originally intended, the film runs a tragic arc in which Stanton becomes the thing he is most pitying of. Zanuck’s insistence on a more redemptive coda does soften the impact, not in a manner that blemishes the film significantly. Even for the picky folks there is a point slightly before the official end which serves as a perfect bitter-edged conclusion to this terrific drama.

A few words on the Criterion blu-ray presentation of the film:

The video comes from a 4k digital restoration that was sourced off a 35mm print element. It looks handsome, nicely reflecting the shadowy cinematography (Lee Garmes). There are instances where some black areas appear flat, and textures somewhat soft, but grain is also evident, indicating that the softness is not the result of undue digital tinkering. The mono LPCM track adequately presents the film’s soundscape, with strong support to the dramatic score (Cyril Mockridge), which brings to my mind some of James Bernard’s throbbing music for Hammer Studios. Extras are significant, including an audio commentary by noir experts Ursini and Silver, a half-hour video essay by the erudite critic Imogen Sara Smith, a very fascinating history of the carnival sideshow by an actual performer-turned-historian Todd Robbins, and a relatively recent interview with Coleen Gray. There is a leaflet with an essay and even a handful of tarot cards representing the film's characters.